THE MOVEMENT OF HERSTORY: KOREAN EMBROIDERY - The Life and Artworks of Young Yang Chung

March 2nd ~ April 27th 2017

Gallery Korea at the Korean Cultural Center New York

(460 Park Avenue, 6th fl., New York, NY 10022)

Opening Reception on Wednesday, March 8th, 2017. 6-8 pm

“Human beings have made two things of the hardest steel. One is the knife, and the other is the needle. The knife cuts, severs, rips, and tears.

Made of the same steel, a needle does the opposite. The needle puts together what has been taken apart, mends what has been worn. It does not separate, but combines; it is not a cessation, but a succession.

A needle looks weaker than a knife, but it is though the power and energy of the needle that [women] have cultivated a territory of life, integrating the worlds of function and adornment.

”

On the Exhibition

Embroidery, rooted in the long history marginalization as utilitarian “women’s work,” has evolved over the past years to a higher form of textile arts.

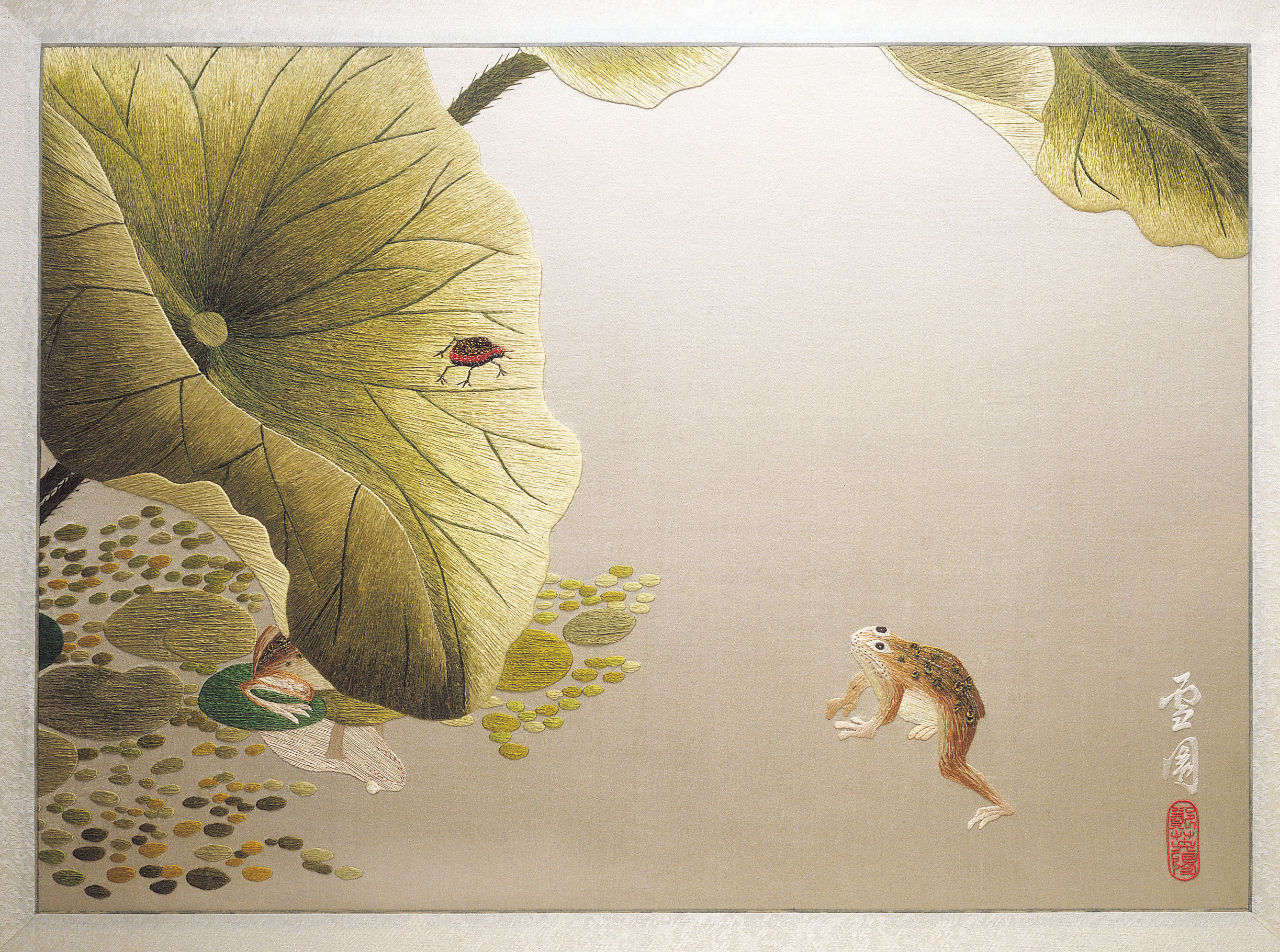

Korean embroidery and its technical, aesthetic excellence has been brought to light by the artist, pioneer, and historian, Young Yang Chung. Small needles and homespun silk threads proved to be immensely powerful in her hands as the tools that not only proved to be a creative outlet, but a means as a viable vocation for Korean modern women.

Boldly crossing the threshold of the women’s quarters (gyubang), Korean women have created a movement by breaking boundaries - both physically and metaphorically - through embroidery.

Elevating the gyubang culture of Korean embroidery, Chung’s ability to “paint with needles” has garnered worldwide attention as she has advanced an art form conceived as women’s work to an important part of textile arts and history.

The Movement of Herstory is a look into the legacy of Korean embroidery through the life and artworks of Chung, now an indelible part of Korean herstory.

Unification (10-panel folding screen)

Young Yang Chung

Korea, 1960s

Featuring Korea’s national flower, the mugunghwa (more commonly known as the “Rose of Sharon”), this screen was commissioned by the Korean government for display in the presidential mansion. Configured in the shape of the Korean peninsula, with the white flowers on the left symbolizing South Korea and the red flowers on the right representing the North, this blossoming branch of mugunghwa expresses the hope for reunification as well the strength and fortitude of Korea’s national spirit, as the mugunghwa is renowned for its power of endurance.

Applying just one square inch of such fine embroidery entails several hours of labor; this screen required over three years to complete.

Photo credit: John Bigelow Taylor

This exhibition is presented as a part of Asia Week New York and also in celebration of International Women's Day 2017.

BACKGROUND OVERVIEW ON KOREAN MODERN WOMEN’S HISTORY

Traditional Korean society confined women to the domesticity as Confucianism was the prevailing social ideology, especially during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), resulting in pronounced male domination. Girls were taught the virtues of daughterhood, wifehood, and motherhood, with primary roles designated within the space of the home. With the opening of the country to the outside world in the late 19th century and as modern schools were introduced to the peninsula, women began to engage in the arts and education, and in turn, public life.

With the establishment of the Republic of Korea in 1948, women achieved constitutional rights for equal opportunities to pursue education and public work. The female labor force contributed significantly to the rapid economic growth that Korea achieved during this time, as increasing numbers of women engaged in professional fields.

With economic development of Korea as a whole, participatory democracy, and expansion of welfare policies, women showed significant contributions to society. In 1998, the Presidential Commission on Women’s Affairs was established and in 2001 expanded to become the Ministry of Gender Equality.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Chung says that needle and thread “proved to be powerful, life-changing tools that carried [her] along a fascinating pathway across time and space.” During Korea’s difficult period of post-war reconstruction, she harnessed her talents to positively impact the lives of many Korean women. With her training in embroidery from a young age, she began to formally teach the art form by establishing South Korea’s first government-sanctioned vocational embroidery school, The Women’s Center, and nurtured a new generation of Korean embroidery artists. The quality of Chung’s works attracted attention in Korea and abroad, leading to commissions to produce works for the presidential palaces in South Korea, West Germany, and Malaysia.

After completing her PhD studies at New York University, she published a series of books that have become invaluable references for the field, and she has taught and exhibited her work throughout the world. In 2004, she founded the Chung Young Yang Embroidery Museum at Sookmyung Women’s University in Seoul, and in 2011 she established the Seol Won Foundation, which seeks to advance the knowledge of textile arts while promoting cultural understanding between the East and West.